The Open Cities Lab team gets to work with a bunch of different types of people, who all recognise that technology can be put to use in solving problems for people who live in cities. This takes different forms, and sometimes it can get a little murky. When do you need a data scientist, and when are you actually asking about policy on a new techy thing that you just don’t understand, so you’ve found your nearest gathering of geeks and thrown the problem at them?

This “muddle our way through” approach will only work for so long — technologically driven changes are knocking on every city and cCity system, and need different approaches and skill sets to respond to them. In this blog post, we try to break down some of the popular ones we get asked about and suggest the types of skills and ecosystems needed in the contemporary urban tech field.

Data products for better services, plans and policies

City governments are big institutions that collect a lot of data. Some of that data is very well structured and stored on large systems (often using well-known applications by proprietary software providers such as SAP). Some of that data is not that well structured, and is sitting on paper, on drives, on computers distributed across these mega, hard to navigate organizations.

At the same time, City governments have lots of problems that they would like to better understand — how can they more efficiently fix all these requests for services? How can they learn from all these requests about where there are systemic problems, and put that insight to use in planning next years’ capital budget? Where is the population growing (in between census counts), where do these people work, how do they move? Where are people particularly vulnerable to heat waves, floods, fires or crime due to overlapping factors of exposure and lack of access to certain services , social amenities and (green) infrastructure? How might transport patterns be impacted by a new land use intervention or labour market trend, and do more taxi licenses need to be issued, or should the land use be directed elsewhere? How will municipal tax revenue be impacted by households moving off-grid…? …

That’s an awful lot of questions, cutting across a lot of different fields. City data science capabilities need to be explicitly interdisciplinary, user/demand-driven, and applied.

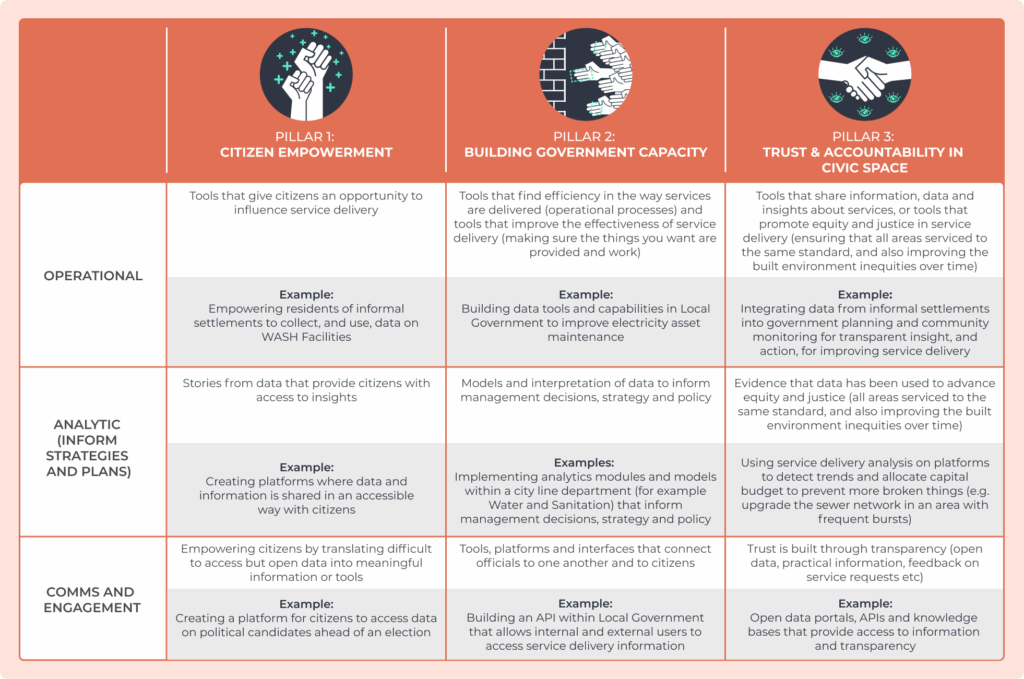

At OCL we organize our work according to 3 Pillars. Below, we give examples of how applying data science within City governments can contribute to these three pillars, at both an operational level, and at a strategy and planning level. We do this through a set of mostly open-source tools that combine data collection (often using a system such as Kobo), data storage and sharing (often using CKAN), data analytics (often using custom Python or R, tools such as Leaflet, or if required by partners’ ESRI, Microsoft of Google based systems), and data communications (data stories). By combining these capabilities, unique products are built for different purposes:

Links to examples:

Analytic (inform strategies and plans)

- Stories from data that provide citizens with access to insights

Example: Creating platforms where data and information is shared in an accessible way with citizens (e.g. here)

Comms and Engagement

- Empowering citizens by translating difficult to access but open data into meaningful information or tools

Example: Creating a platform for citizens to access data on political candidates ahead of an election (e.g. here)

- Trust is built through transparency (open data, practical information, feedback on service requests etc)

Example: Open data portals, APIs and knowledge bases that provide access to information and transparency (e.g. here)

Most City governments have people with data science skills working for them in a distributed way — across departments, for service providers, for sellers of solutions(™). Increasingly, Cities, like other large organisations, are recognising the need for dedicated capacity to a centre of excellence for data science, who lead:

- An Data Strategy, and guidelines with regards to data governance, architecture, and change management (including how data quality, data sourcing, data privacy compliance, and interpretation of data will all be improved over time)

- Implement these through a pipeline of “use cases” — real projects that take line departments with a real operational, analytical or communications challenge through a process that improves data quality, data skills and culture, complies with new standards for governance and architecture, while producing a cool, useful “clicky-something” that gives people the just-in-time information and insight that they need to do their day job a bit easier, faster or better.

<<”Clicky-something” — user-speak for dashboards, interactive maps, dynamic models, data-bots, etc>>

At OCL we believe that models can be right or wrong (based on the quality of the data, and the assumptions framing the analytics), but no model is going to replace the governance work that is needed in Cities. They are tools in improving insights and decision making — an asset to managers and citizens alike.

Chat back: Communications Apps

A big part of life in any community is representation in processes and this is related relating to how that community is run — some people just want to be able to report and have feedback about services that break from time to time, and others are more actively engaged in sharing inputs inputting into plans and budgets.

Just like many of us do our banking from our couch, we now expect to do our civic engagement from there too. A lot of Cities around the world, and also in South Africa, are experimenting with some form of digital communication tool or toolset.

These range from fully downloadable apps, like Ekhurleni, George or Drakenstein, to offerings that integrate with other popular communication channels — like SMS and Whatsapp bots.

Internationally, tools for community engagement, spatial and district planning, and integrated civic management are advanced.

Of course how we ask citizens to input into these channels, and what they enter, all becomes potential structured data — for those data products discussed above.

Key considerations when exploring these “new screen deals” or the “digitisation of civic life” in our context fundamentally relates to equity and inclusion: how the user interfaces are designed, what questions (data fields) are and are not included, access to internet, screens and skills to utilize these tools should not skew representation and/or service delivery outcomes. This is why OCL has a dedicated Gender and Social Inclusion champion, and we spend a lot of time in all of our work querying the potential to do harm, exclude, perpetuate data gaps or contribute to interpretation biases.

e-Things

It’s not so rare that midway through a call on data governance, someone will throw in a question about sensors in street lights, drones for security, or what to do about e-scooters. This has been on someone’s mind, and the guy with the beard must know the answer, right?

This element of the urban technology agenda is about digitally enabled infrastructure — everything from “Internet of Things” sensors that enable remote controlling and monitoring of water quality, traffic management, street lights, utilities use, security surveillance, movement of people and goods… These can be in the hands of the public sector (water management devices, fleet tracking, CCTV), private sector (CCTV, proprietary but mission-linked sensors), or civic technologists (networks of civic air quality monitoring). The technology itself is neither inherently “good” or “bad” — its outcome is largely dependent on how it is put to use, and may require regulation to balance the contribution to shared value and social equity.

Other “disruptors” in this category are advances in technology that change the traditional way people use public goods, services or spaces. E-hailing, delivery services, and e-scooters/bikes, off-grid solar and water are the most dominant currently, while virtualisation of services, training, and robotic infrastructureis the next frontier.

<<We love this FutureofUrbanTech explorer built by Cornell University’s Urban Tech Hub>>.

People in this field are developing frameworks for understanding new technology entrants, and rules for knowing when to impose an obligation on them (some sort of license, fee, limitation on terms of use etc); when to enable (provide dedicated services and infrastructure), and when to co-invest or integrate into the public service.

The people working in this area have foresight abilities, understand technology business models, and understand the vulnerability and exposure of critical public goods and services, liability, and policy and strategy making.

But when is it “Civic tech”?

Another common challenge we are seeing is the public sector conflating their identified “data gaps” with “civic tech will solve that”. What this looks like is in a paragraph somewhere in a report about the need for gender disaggregated data, is something about SafetyPin apps, or in a report about the need for better data on informal businesses, is something about the opportunity to digitize informal businesses through eCommerce.

While it is true that these sorts of digitisation or civic tech tools have the potential to generate data that can be a great addition to official data sets, their primary impact, interest and sustainability is built around a different user — and this needs to be understood and integrated with if long-term shared value is to be created.

So what is “civic tech” — our team member Ella wrote about it here. At its core, it is citizens putting technology to use to access services, build representation, or address issues in their communities. It is communities creating their own networks of pollution monitors (OCL learnt how, we love this group of young civic scientists, and this global map). It is residents in informal settlementsusing Whatsapp based forms to do social audits. It is urban managementapps.

Broader than the creation of specific tools, the civic tech community also includes well-informed citizens who are concerned with processes for governing urban tech — who want technology to be applied in ways that empower and include the disempowered, and who want to check the reach of technologies launched by those in power. These communities are active in regulatory spaces as much as they are busy creating decentralized autonomous organisations.

The local eco-system in South Africa

In some ways, there is a “race to be the smartest” happening between Cities — but our Cities are a long way from being integrated digital platforms, let alone with the capacities to anticipate and govern technological advancements internally and externally.

Given that a) most Cities are struggling with general capacity and resource constraints in a context of urgent and overwhelming developmental need and b) this is a new and diverse field — we, at OCL, believe that innovation and learning in this field should not be hoarded by Cities, but should be shared openly and unlocked to lift the overall capacity within the broader field, and improve governance in all South African metros.

Unlike “traditional” urban disciplines which have professional bodies offering registration, continuous professional development etc, the urban tech areas described in this post do not fit neatly into existing forums and structures. Where do people working on these problems, developing solutions in these spaces turn to learn, connect or share?

In our experience, they you are distributed across government line departments (working with economic data, using GIS, and as engineers who’ve taught yourselves to code). They are You’re also working in Civic tech orgs like OCL, OpenUp, or NGOs that use technology like VPUU and IBP. They’re You’re leading the development of new practices from intermediaries like SACN, CSP, CTIN and they’re you’re developing skills and products through private coding academies and the private sector tech industry (rich and diverse including “big” and “little” tech).

Opportunities for learning areas

From OCL’s perspective, we see potential for these groups to be learnings in the following areas:

- How are Cities operationalising data tools to help make service delivery more efficient, effective and equitable?

- How are citizens developing and leveraging technology to improve representation and access to process, information and services?

- How are role players involved in urban governance regulating and/or enabling urban technology to ensure the safety and privacy of citizens, while also integrating the advantages of technology for better mobility, utilities, and shared spaces?

- What is the “next frontier” in terms of Cities as truly integrated platforms, and where will that be built from — is it private sector, DAOs, or City-led?

We’d love to have these conversations with you. Contact us.